9 Tips for Better Planning and Estimation in the Enterprise

Consider two bike journeys: your daily commute to work versus a cycling adventure through Patagonia. For your commute, you can estimate arrival time within minutes based on experience. But planning a multi-week expedition through unpredictable terrain, weather, and conditions requires a completely different approach. You need flexibility, contingency plans, and the ability to adapt as conditions change.

Enterprise planning works the same way. Simple or complicated tasks are like the daily commute - predictable and easy to estimate. Complex initiatives are like the Patagonia adventure - requiring adaptive planning strategies that accept uncertainty rather than fight it.

Planning in the Simple and Complicated Space

Back to our bike metaphor: Planning your daily commute is straightforward. Repeat it often enough, collect data on travel times, identify the extreme points (high traffic on special days), and you’ll reliably arrive on time for your meetings. Simple and complicated tasks work this way - they’re predictable, repeatable, and easily estimated. Once you understand them, they become a no-brainer.

Most enterprises handle simple and complicated work reasonably well. The real challenge lies elsewhere: as markets evolve faster and uncertainty grows, the complex space continuously expands. This is where traditional estimation, prediction, and planning methods break down.

Planning in the Complex Space

The Patagonia adventure represents this complex space - environments where every day brings new terrain, unexpected weather, and unforeseen challenges. This is where simple, time-based planning fails and adaptive approaches become essential.

The challenges of planning in uncertain environments are not new. The Agile community has developed specific practices for planning and estimating in complex product development - techniques like iterative planning, relative estimation, and velocity-based forecasting that embrace uncertainty rather than pretend it doesn’t exist.

“No plan survives first contact with the enemy.”

But long before the Agile Manifesto, military strategists understood the fundamental problem. Helmuth von Moltke, a Prussian field marshal, captured this reality in 1871 when he stated: “No plan of operations extends with any certainty beyond the first encounter with the main enemy forces.”

In business, your “enemy” might be fair competitors in the market, emerging technologies like AI, or simply the inherent complexity of product development. The Agile Manifesto addresses this directly: responding to change over following a plan.

This doesn’t mean plans have no value. It means we must prioritize adaptability over rigid adherence to predetermined paths.

The more complex the task, the greater the deviation from the plan and the lower the accuracy of estimates. This is not a failure of planning but a characteristic of complex work.

So how do we estimate and plan effectively in this complex space where most enterprises operate today? Here are nine practical tips that challenge conventional wisdom about estimation and planning.

Tip 1: Estimations Are Overestimated

Humans are optimists. Well, that’s why we’re human. But this creates a cognitive bias in estimation (see Planning Fallacy).

Moreover, the relationship between time spent estimating and estimation accuracy is not linear. It follows a saturation curve. After a certain point, spending more time on estimation doesn’t improve accuracy. In fact, it can decrease accuracy as people influence each other.

In short, when someone asks “how accurate is your estimation?” most people answer with a too optimistic number. In reality, it’s much worse.

The practical conclusion: invest less time in estimation.

The probability that you’re over-investing in estimation and not gaining better accuracy is high. When choosing between detailed estimation techniques or simpler approaches, err on the side of simplicity.

Tip 2: We Seek Security - Planning and Estimating Is Often an Excuse Not to Start

Humans naturally avoid risk. This makes evolutionary sense - why take unnecessary risks? In complex environments where uncertainty is high, this tendency becomes stronger.

Today’s risk in business is typically a difficult conversation with your manager, not physical danger. Yet we still avoid starting.

Several perspectives help overcome this paralysis:

Planning and estimation must be paid for. The time spent on detailed plans and estimates consumes budget. Often, direct implementation would provide more certainty faster.

Only implementation provides absolute certainty. Each implementation validates or invalidates a hypothesis.

Experiments can increase knowledge. Prototypes and spikes can improve planning accuracy. But beware: implementation may still be cheaper than extensive experimentation.

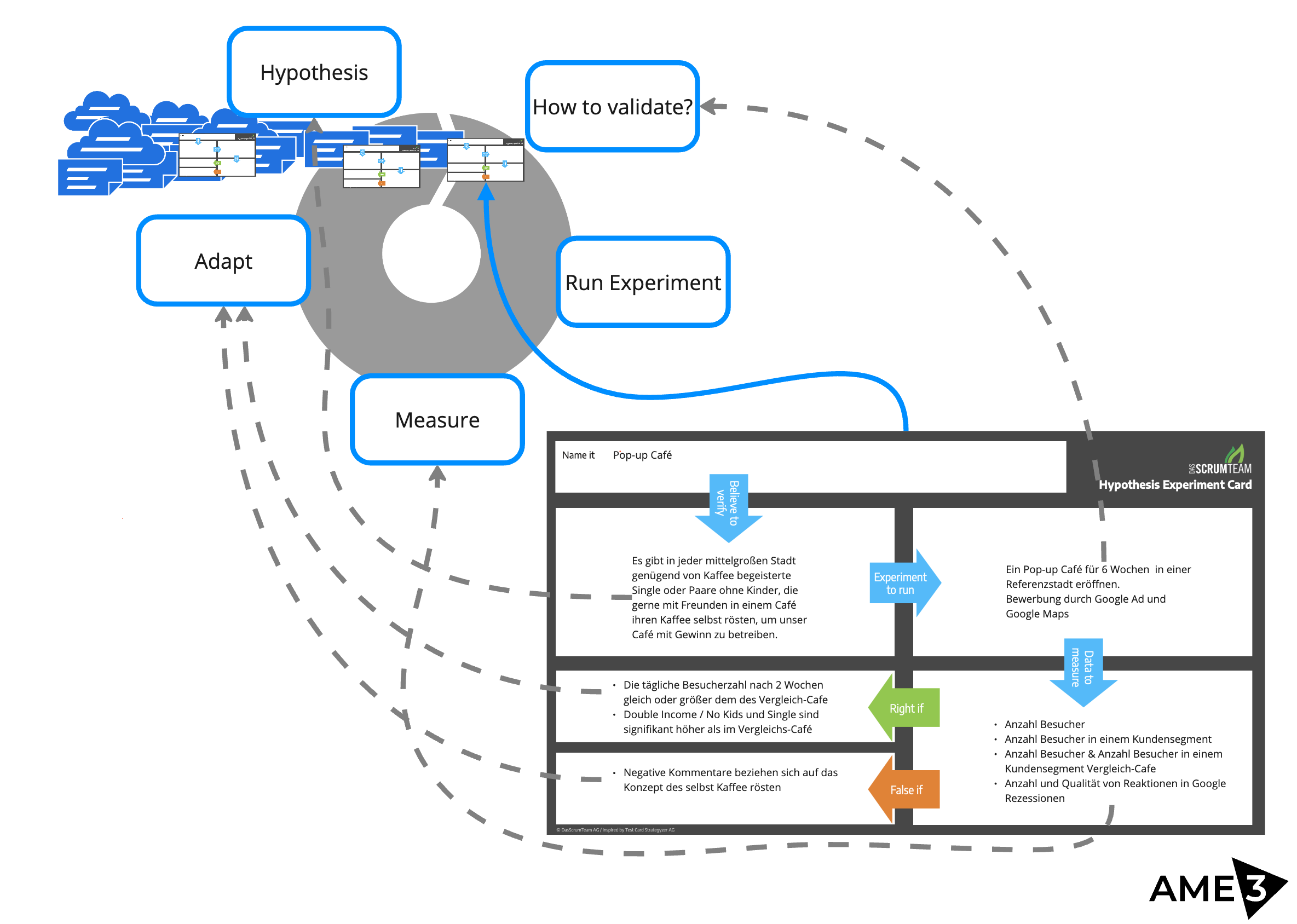

Hypothesis Experiment Cards as Improvements in a Backlog

Hypothesis Experiment Cards as Improvements in a Backlog

Use our hypothesis experiment cards when you need more certainty before full implementation. But always ask: would direct implementation with its associated risk actually be less expensive?

Scrum and AME3 are fundamentally empirical control processes. Backlog entries are hypotheses. Advancing in a Match or Sprint generates data and validates them.

Tip 3: Use Different Estimation Methods for Each Level

Don’t try to create a single estimation hierarchy from enterprise goals down to individual tasks. This classical project structure plan thinking works in simple environments but fails in complex ones where changes happen too fast.

Instead, use lightweight estimation methods at each organizational level that provide sufficient accuracy with minimal effort:

Enterprise level - Strategic goals and initiatives

- Use relative comparison to past goals, initiatives, or projects

- Consider dimensions like strategic relevance, business benefit, organizational impact, complexity, and CapEx

- Spider diagrams can visualize multi-dimensional comparisons and make relative planning and decision making easier.

Product/Backlog level - Features and stories

- Relative estimation (Story Points with planning poker or bucket estimation)

- Velocity-based planning

- No estimation (counting items, see Tip 7)

Task level - Daily activities

- Time-based estimates using natural time boxes (days)

- Pull-based planning

Each level has its own reference frame and planning horizon. Don’t try to roll up task estimates into story points, and don’t try to estimate enterprise initiatives by detailing them in backlog or project plans.

Tip 4: Choose the Right Reference for Estimation

Relative estimation works because humans find it easier to compare things than to measure them absolutely.

Time is actually a poor reference for many situations:

- How long will a colleague take?

- How long will I take tomorrow when I’m more experienced?

- It’s like the ur-meter in Paris changing its length all the time. For a precise measurement, you need an even more precise reference.

Better references include:

Other work items - Planning Poker and bucket estimation compare stories to each other, not to abstract time measures.

Metaphors - Using animals (elephant, cat, mouse) creates mental images. The brain processes relative sizes more naturally than abstract numbers.

Completed work - What we’ve already delivered provides the most reliable reference frame.

The key is that your reference stays stable even as your team’s capability evolves. A size 5 story is always five times larger than a size 1 story, even if the team gets faster at delivering both.

Tip 5: Never Use Estimates for Performance Measurements

What you measure is what you get.

If you measure team performance using velocity based on Story Points, teams will increase their Story Points. Not by working faster, but by estimating higher.

Real example: An organization measured Scrum Masters by their teams’ commitment achievement (planned Story Points vs. delivered Story Points). Result? Teams became slower on paper. They planned less per sprint to ensure they always met commitments.

Another anti-pattern: Using velocity as a performance KPI encourages teams to inflate estimates or deliver more features of poor quality that nobody needs.

Estimates should only be used for planning future work, never for performance evaluation, rewards, or punishments.

This is also why time-based estimates are problematic. Humans are paid by time. When you ask for time estimates, you’re asking people to estimate something directly tied to their compensation. This creates perverse incentives.

Use estimates for their intended purpose: understanding where you’ll be in the future. Don’t use them to judge whether teams are “good” or “bad.”

Tip 6: Velocity Is the Better Planning Foundation in Complex Environments

Relative estimation with abstract numbers (like Story Points) keeps estimates stable longer than time-based estimates. This allows teams to benefit from increasing accuracy, without constantly reworking their estimates.

Here’s why: After three sprints, your team gains experience and becomes more accurate. With time-based estimates, you’d need to rework your entire plan each sprint:

- Sprint 1: Estimated 100 days

- Sprint 2: Actually need 130 days (update all estimates)

- Sprint 3: Actually need only 60 days (update all estimates again)

With relative estimates and velocity:

- Sprint 1: 50 Story Points to release in Backlog, velocity 10 per sprint = 5 sprints

- Sprint 2: 8 Story Points completed. Still 42 Story Points to release, velocity now 8 per sprint = 5.25 sprints

- Sprint 3: 12 Story Points completed. Still 30 Story Points to release, velocity now 12 on average = 2.5 sprints

The estimates don’t change. Only the velocity changes. Your five-point item is still five times larger than your one-point item. This makes planning dramatically more stable.

Tip 7: Scrum Has a Built-In Estimation (But Few Know It)

Many people don’t realize Scrum has a built-in estimation technique. It’s not Planning Poker.

The built-in estimation is pull-based planning.

Think of the childhood game of guessing how many peas fit in a jar. Sprint planning works the same way. The sprint is your jar. Backlog items are your peas. You estimate by pulling items into the sprint until it’s full.

This pull-based approach uses a known, fixed timeframe as the reference. A sprint is typically a month or two weeks. We know from experience what we can accomplish in such timeframes.

The modern term for this is “No Estimates” - but it’s actually still estimation, just implicit rather than explicit.

For this to work, you need fixed iterations like Sprints or Matches. Without them, pull-based estimation doesn’t function.

Calculate velocity by counting completed items. If Backlog items are sized to fit within a sprint through refinement, they naturally become similar in size. Count them: 10 cards completed in a sprint means your velocity is 10 cards per sprint.

This is simpler for new teams to learn than complex estimation techniques like Planning Poker, and in practice, accuracy is comparable.

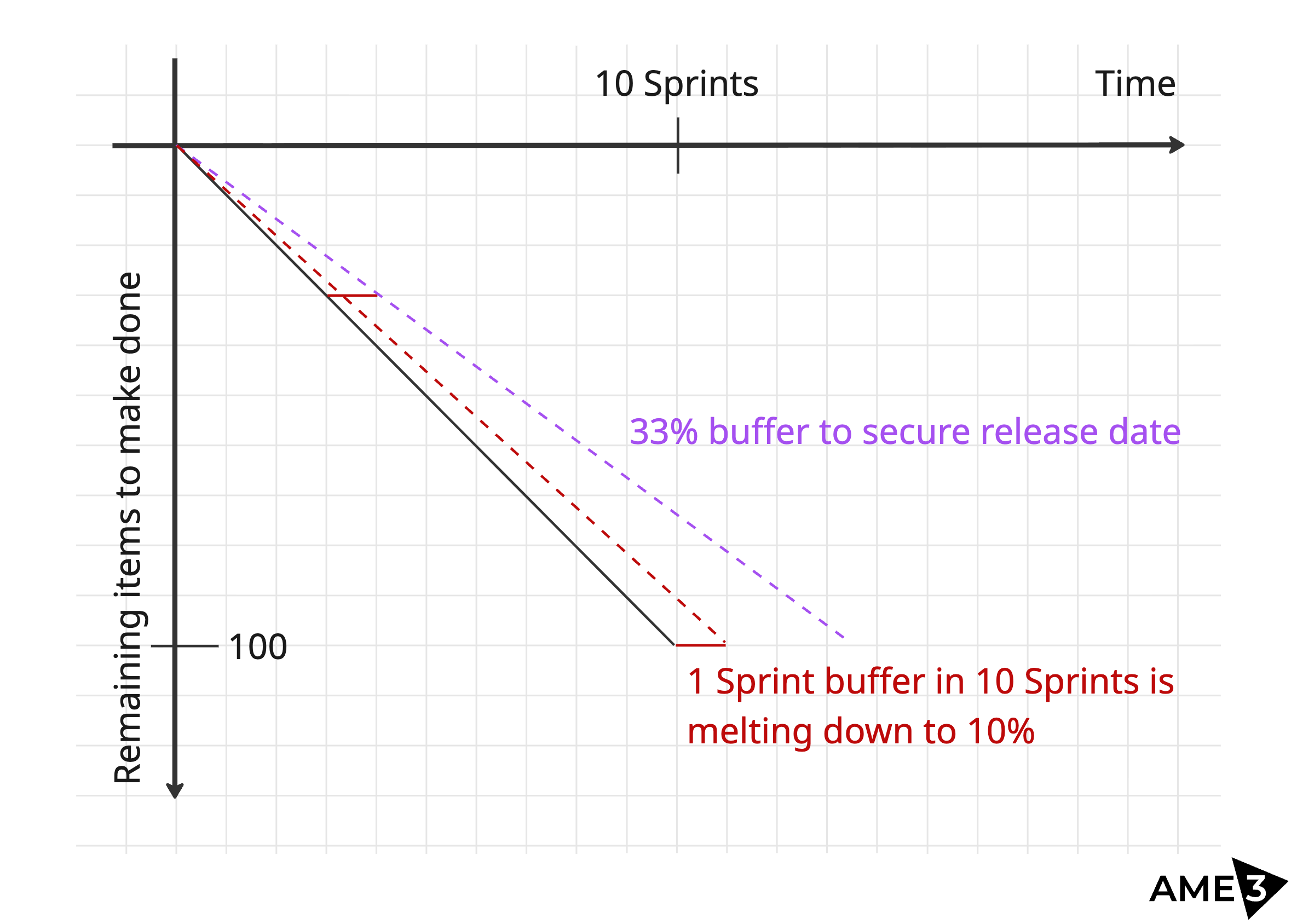

Tip 8: Never Plan Absolute Buffers

One of the most common mistakes in planning is using absolute buffers instead of relative ones. The difference is critical.

Consider a burn-down chart where your team has an average velocity of 10. So in 10 sprints it can complete 100 items. If you add a buffer of one sprint to a three-sprint timeline, that’s roughly 33% - already optimistic for most projects.

Consider a burn-down chart where your team has an average velocity of 10. So in 10 sprints it can complete 100 items. If you add a buffer of one sprint to a three-sprint timeline, that’s roughly 33% - already optimistic for most projects.

But here’s the problem: If you’re planning 10 sprints ahead and still use just one sprint as a buffer, you’re down to 10% contingency. For 20 sprints, it becomes 5%.

Buffers must scale proportionally with timeline length.

For a 33% buffer, you need:

- 4 sprints of buffer for 10 sprints of work (count only full sprints, so 3.3 becomes 4 sprints)

- 7 sprints of buffer for 20 sprints of work

Remember: that’s only 33% contingency, which is actually optimistic for most enterprise projects.

Tip 9: The Value of Planning Lies Not in the Plan Itself, But in the Exchange

“Plans are worthless, but planning is everything.” — Dwight D. Eisenhower

The longer version adds context: “In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.”

The planning process generates insights. The plan itself is just a snapshot.

This is why techniques like Planning Poker remain valuable even when simpler methods work. The discussion when people show different estimates reveals hidden assumptions and risks. This extreme value analysis surfaces critical misunderstandings.

Planning forces engagement with the future and its uncertainties. The conversation among participants creates shared understanding that no written plan can capture.

If your estimation technique creates good communication containers where teams and leaders discover misalignments and build shared understanding, it’s valuable regardless of the accuracy of the estimates produced.

But always ask: could we have this exchange without the estimation technique? If the technique only provides value through communication, perhaps there’s a lighter way to achieve the same conversation.

Key Takeaways

- Invest less time in estimation - Diminishing returns set in quickly

- Implementation provides certainty - Don’t let planning become procrastination

- Each level needs its own method - Don’t roll up task estimates to enterprise plans

- Choose stable references - Time changes; relative size doesn’t

- Never measure performance with estimates - What you measure is what you get

- Velocity beats time estimates - Keeps plans stable as teams learn

- Pull-based planning is estimation - Scrum has this built in

- Use relative buffers, not absolute ones - Scale contingency with timeline length

- Value the process over the plan - Planning creates shared understanding

Planning and estimation in complex environments requires accepting uncertainty, using lightweight techniques, and focusing on learning over precision. The goal is not perfect accuracy but sufficient confidence to make good decisions.

Related Sources

- Planning Fallacy - The cognitive bias that causes systematic underestimation

- Overconfidence Bias - Why we overestimate our estimation accuracy

- Plans are worthless, but planning is everything

- No plan survives first contact with the enemy